The Erratic Radio is a re-designed radio that ‘listens’ not only to normal radio frequencies but also to those around the 50Hz band – frequencies emitted by active electronic appliances. As a reaction to increasing energy consumption, the functional behavior of the radio becomes erratic and unpredictable, thus conceptually relating to the unpredictable, uncontrollable, and intangible effects of increasing energy consumption.

Morozov thinks out loud about the utility of this strange product: “Imagine hungry radio listeners bringing the radio set into the kitchen to grab some food without missing their favorite show,” he writes. “As they move around the kitchen, the show gets increasingly difficult to hear, as the sound reflects the strength of the electric magnetic field in the the current location.”

Most radios don’t consume that much energy, but the point here is to raise awareness about the costs of the typical array of devices we deploy. As designers Anders Ernevi, Samuel Palm, and Johan Redström elaborate:

As you sit at your office, you switch on the radio and tune in the preferred station. Listening to the music for a while, you realize you need to turn on the light. Starting to turn on a series of desk lamps, the radio gets increasingly noisy as it shifts away from the selected frequency. Only by turning the lights off again, returning to the original state, will the radio work properly again….

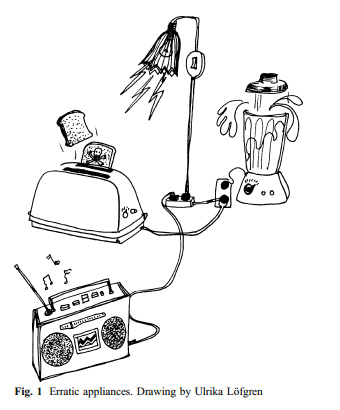

The trio posit a whole array of “erratic” gadgets designed to challenge the very “distant” sense most consumers have regarding skyrocketing energy use, including erratic television sets, erratic toasters, and erratic blenders. Yet more on the radio:

The trio posit a whole array of “erratic” gadgets designed to challenge the very “distant” sense most consumers have regarding skyrocketing energy use, including erratic television sets, erratic toasters, and erratic blenders. Yet more on the radio:

In order for the radio to tune out and behave erratically, this center frequency needs to be shifted. The ‘erratic-ness’ of the radio is thus created through hacking into the radio channel selection filter, allowing a microcontroller to slightly alter the frequency chosen. In order for the radio to react to energy usage, a sensor has been devised, measuring the electrical fields around the radio. This provides a sense, not only for the actual consumption, but also for the electricity that surrounds us in our everyday life depending on where the artifact is placed. This kind of sensing does not provide accurate measurements of consumption, but it gives an additional feature of mobile measurements.

“We are suckers for various technologies,” Morozov notes, “but we rarely recognize that their use is only made possible by vast sociotechnological systems, like water supply and now cloud computing. Thus does the author praise the “strangeness” of these gadgets. “The strangeness is deliberate: it seeks to introduce aspects of risk and indeterminacy into the use of such devices.”

I suppose that it would be simpler just to set up some kind of energy overuse alert system in one’s house—a flashing red button or something similar. But I wonder how many people would soon shrug their shoulders and experience the alert as part of the background auto-flow of life.

A radio, on the other hand, that suddenly gave me Rush Limbaugh rather than my local classical station . . . now that would get my attention.