The “what is radio” debate resurfaced earlier this month. Do Pandora and other streaming music services qualify as “radio”? Jennifer Lane, President of RAIN Summits, pronounced the question irrelevant at her Audio4cast blog. “I say who cares whether it’s radio or not,” Lane declared.

The “what is radio” debate resurfaced earlier this month. Do Pandora and other streaming music services qualify as “radio”? Jennifer Lane, President of RAIN Summits, pronounced the question irrelevant at her Audio4cast blog. “I say who cares whether it’s radio or not,” Lane declared.

But some weeks earlier Pandora’s Tim Westergren posted a commentary explaining the significant differences between his service and AM/FM broadcasting. The essay focused on Westergren’s favorite regulatory subject: performance royalties, and how they’re calculated for Pandora (as opposed to how they might be calculated for FM radio stations if they were equally tithed).

Westergren wrote:

” . . . we need to clarify what a ‘spin’ on Pandora means. Each spin on Pandora reaches a single person, compared to a ‘play’ on FM radio that reaches potentially millions of people. In other words, a million spins on Pandora might be equivalent to a single play on a large FM station.”

The point: most Pandora fans listen to unique streams that reach only their individual ears. They, millions of them, get their own listening private room. AM/FM listeners, on the other hand, tune into a single stream that transforms them into something called an “audience.” All kinds of possibilities flow from this latter process: community, solidarity, social cohesion—potentially nice things. It is a big difference, I think.

But there are important moments when Pandora and similar services become like radio, if not the very thing itself. First: when they serve up their own curated channels. Pandora is particularly good at this during holidays like Halloween. Second: when you promote your own social media music channels or playlists to the world via a Pandora or some similar music database service. And that’s why what I call “exportability” matters.

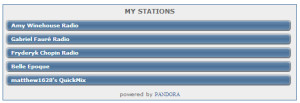

Exportability is the ease with which you can publish your Pandora channel, or a Spotify playlist, or an All Access link to your blog, Facebook page, or Twitter stream. It is also the extent to which you can customize that interface. At present, there isn’t a lot of exportability out there. Pandora offers you customizable html code to publicize your stations, but clicking any of your links takes you right back to Pandora central. Spotify lets you export playlists (see below), but makes it difficult to visually alter them.

Exportability is the ease with which you can publish your Pandora channel, or a Spotify playlist, or an All Access link to your blog, Facebook page, or Twitter stream. It is also the extent to which you can customize that interface. At present, there isn’t a lot of exportability out there. Pandora offers you customizable html code to publicize your stations, but clicking any of your links takes you right back to Pandora central. Spotify lets you export playlists (see below), but makes it difficult to visually alter them.

Google All Access lets you post a hyperlink to Google Plus, or you can take the link elsewhere. Last.fm says it lets you export tracks via a service called playlistify, which, last time I checked, was a dead link.

Despite these limitations, music application users do very creative things with what they have been given. There are so many public Spotify playlists that sites aggregate and post news items about them. Among these are the Spotify Collection and the Pansentient League. One of my less glitzy favorites: the Spotify Classical Playlist site of Ulysses Stone, who lives and presumably works in Beijing.

I want to see more of this. Imagine if you could export Turntable.fm rooms—pick up some iframe type html code that allowed you to see and operate your room not just in the turntable.fm environment, but via windows that appeared on your blog. Maybe you would have to pay extra for such technology. I think it would be worth it to allow users to ever more elaborately turn Spotify playlists, Pandora channels, and other venues into sophisticated radio stations, serving real audiences on the public Internet instead of dwelling behind individualized walled gardens.

I want to see more of this. Imagine if you could export Turntable.fm rooms—pick up some iframe type html code that allowed you to see and operate your room not just in the turntable.fm environment, but via windows that appeared on your blog. Maybe you would have to pay extra for such technology. I think it would be worth it to allow users to ever more elaborately turn Spotify playlists, Pandora channels, and other venues into sophisticated radio stations, serving real audiences on the public Internet instead of dwelling behind individualized walled gardens.

Jennifer Lane wrote on her Audio4cast blog:

“It’s all about the consumers. They are deciding what they want to listen to, and what device they will listen on. And they’re not debating whether or not it’s radio. They’re simply selecting the content that is most appealing to them. To them, the debate about whether it’s radio is irrelevant. And so it should be to everyone else. The new generation has no idea which tv stations are broadcast and which ones are cable. They don’t think about it and they don’t care. It’s all tv to them.”

For sure, many consumers may not know the difference between cable and broadcast TV, but they can distinguish between stations that run infomercials and those that offer fresh drama, live news, and public affairs. The question is not whether consumers should be able to choose; it is whether they’ll have choices. As streaming radio becomes ubiquitous—just about every big company (including Apple) offering huge databases of tunes—what may set these services apart are the degree to which users can creatively deploy them to become broadcasters themselves.