“Have you ever had to wait for a prescription at the pharmacy, and watched it being made? Gram by gram or decigram by decigram, the pharmacist weighs out all the substances and powders needed for the finished medicine on a scale with very delicate weights.”

So began Walter Benjamin’s October 31, 1931 Radio Berlin broadcast, the subject of which was an earthquake, of all things. How, you might ask, did he get from his rather pedestrian question about powders and pills to the Great Lisbon Earthquake of November 1, 1775?

So began Walter Benjamin’s October 31, 1931 Radio Berlin broadcast, the subject of which was an earthquake, of all things. How, you might ask, did he get from his rather pedestrian question about powders and pills to the Great Lisbon Earthquake of November 1, 1775?

“I feel like a pharmacist when I tell you my stories in my radio broadcast,” Benjamin continued. “My weights are the minutes, and I have to weigh them with great precision, so many of these, so many of those, to get the balance right.”

You see, he explained, if he just described the earthquake one incident after the next, “I doubt you’ll find it very amusing.”

‘Amusing?’ I exclaimed to myself after reading those words. Who expected me to be amused by one of the worst temblors in history? But Benjamin was explaining his sense of the nature of radio, a medium that he felt did not have the time to narrate events like a history book. It had to get to the point. And the Lisbon Earthquake of 1771 had not one point, Benjamin thought, but four.

First, he continued, we remember the quake not just for its size, but that it destroyed what was then one of the greatest cities in history. Portugal in the mid-18th century was one of the colonial powers. Not until the 1960s and 1970s would it finally lose its holdings in India and Africa. “The destruction of Lisbon at the time would be comparable to the destruction of Chicago or London today,” Benjamin noted.

Second, people experienced the catastrophe all over Europe and Africa. It was felt in Finland. It was felt in what is now Indonesia. “The strongest tremors ranged from the coast of Morocco on one side to the coasts of Andalusia and France on the other,” Benjamin disclosed. “The cities of Cadiz, Jerez, and Algeciras were almost completely destroyed.”

Third, eye witnesses from the time insisted that all kinds of strange natural phenomenon preceded the catastrophe: hurricanes, cloudbursts, floods, and “massive of worms emerging from the earth.”

Fourth, we have generations of observers chronicling and remembering the quake in pamphlets that they distributed as long as 150 years after the fact. The German philosopher Immanuel Kant collected accounts of the fateful day. An Englishman wrote a lengthy description of his flight from his Lisbon apartment to a cemetery that he thought might be safer:

“From the hill of the cemetery I was then witness to a horrific spectacle: on the ocean, as far as eye could see, countless ships surged with the waves, crashing into one another as if a massive storm were raging. All of a sudden the huge seaside pier sank, along with all the people who believed they would be safe there. The boats and vehicles so many people used to seek rescue fell into the sea.”

Benjamin served up all this information, I should add, for a children’s radio show. I guess he decided that the kiddies needed a good scare that Saturday morning. But what I find most intriguing is the author’s sense of radio time. “So much for that fate day, November 1, 1775,” Benjamin concluded. “The calamity it brought is one of the few that mankind still faces as helplessly now as one hundred seventy years ago. . . . My twenty minutes have come to an end. I hope that they did not pass too soon.”

For Walter Benjamin, chronological time and radio time were two different phenomena, and the later literally had no time for the former.

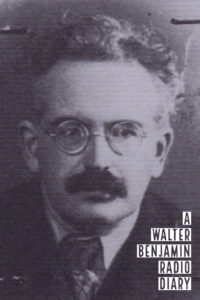

This the fourth installation of my Walter Benjamin radio diary.