Lorenzo Milam, who passed away on July 19, led a fascinating life, evangelizing and launching numerous community radio stations and also championing the rights of people with disabilities. Like many in the community radio world, he got his start in college radio, although that part of his radio history is rarely told.

Milam’s first foray into radio was at Yale University’s campus only carrier current radio station WYBC 640 AM during the academic year that he was a student there, from 1951 to 1952. In Rebels on the Air, Jesse Walker writes, “When Milam entered Yale in 1951, he ‘heeled’ at its student station. That meant he did a bit of everything: writing news, selling ads, engineering, announcing. The outlet was run like a commercial station…”

This apprenticeship period at WYBC even featured organized challenges, with the reward being membership in the radio station. A student newspaper account at the time went into detail about a five to six week fall “heeling competition” in which “each heeler will have an opportunity to produce, announce, and engineer his own programs and work in either the business, news, public relations, records, sports, or technical departments.”

During the 1951-1952 school year, when Milam was involved with WYBC, the student radio station broadcast from 7am (starting with the wonderfully named morning music show, the “Yawn Club”) to 1am on most days, airing a mix of news, music (“Cavalcade of Jazz,” opera, symphonies, “National Hit Parade,” etc.), and sports shows and specials, including faculty talks, “Yale Sings” (spotlighting the numerous undergraduate singing groups), “The Style Show,” and a program that played music from Broadway musicals.

The October 20, 1951 WYBC schedule included “Heelers’ Hacktime” for the majority of the day, sandwiching the broadcast of a Yale vs. Cornell football game in the afternoon. Perhaps Milam was part of this crew of radio trainees taking the helm of the station on this particular Saturday. A few weeks later, representatives from the station headed to Harvard for a meeting of the Ivy Network, a consortium of campus radio stations that banded together to share programming, including sports broadcasts. The Harvard Crimson reported on the November, 1951 convention, which, “…accepted a contract under which the Ivy stations would broadcast the nationally-heard ‘Philip Morris Play house’ over specially installed telephone lines from the National Broadcasting Co.”

Luckily for us radio historians, WYBC’s publicity department produced a film about the station in the 1950s. Filmed by a member of the class of 1955, it covers a day in the life at the station on a fall Saturday, likely in November, 1952. As I watched This is College Radio (1956) – WYBC Yale Radio & the Ivy (Radio) Network, I could easily imagine Lorenzo Milam in the radio studio a year prior. The college radio time capsule provides a glimpse of the formal and professional nature of student radio station WYBC during a time when many college radio stations, particularly campus-only AM stations, aired commercials.

The film outlines the rigorous training program for Yale’s “most popular extracurricular” activity, which was described in the 1952 yearbook as “the fastest growing and largest organization on campus.” Based on the film, shows were quite structured. The sole program where hosts were able to spin their own records without an accompanying engineer was the evening all-request program, “Stardust,” which was a coveted slot for a senior DJ dubbed the “Starduster.” Perhaps the polar opposite of that show was programming piped in by Muzak, described in a 1952 yearbook entry one of the year’s “significant innovations,” as it allowed WYBC to increase its hours of broadcasting. The service facilitated the airing of “quiet, instrumental music for the studious” during mornings and early afternoons.

Although a non-profit organization, advertising was important for WYBC in the early 1950s, with seven sponsored daily newscasts. In the film, one can spot a poster for cigarettes on the wall of the station (a bit of a Lucky Strike-sponsored 5 o’clock news show is also shown) and schedules during Milam’s stint at WYBC included the aforementioned “Philip Morris Hour” and “Ford Symphony Hall.” A local bottle shop encouraged students to not only pick up some deals on beer and French wine but to also, “Tune in WYBC 11:30 every night for Your Sports Final” in its 1951 ad in the Yale Daily News for Chapel Liquor Shop. For Milam, this buttoned-up experience at WYBC helped him get a gig at a station back home in Florida: WIVY-AM in Jacksonville, where he worked for a year after leaving Yale.

Milam became quite ill with polio and did not return to college radio until he arrived at Haverford College several years later. From 1955 to 1957 he participated in the campus-only radio station WHRC and this is where our collective radio pasts converge, as we share both a radio and a college alma mater.

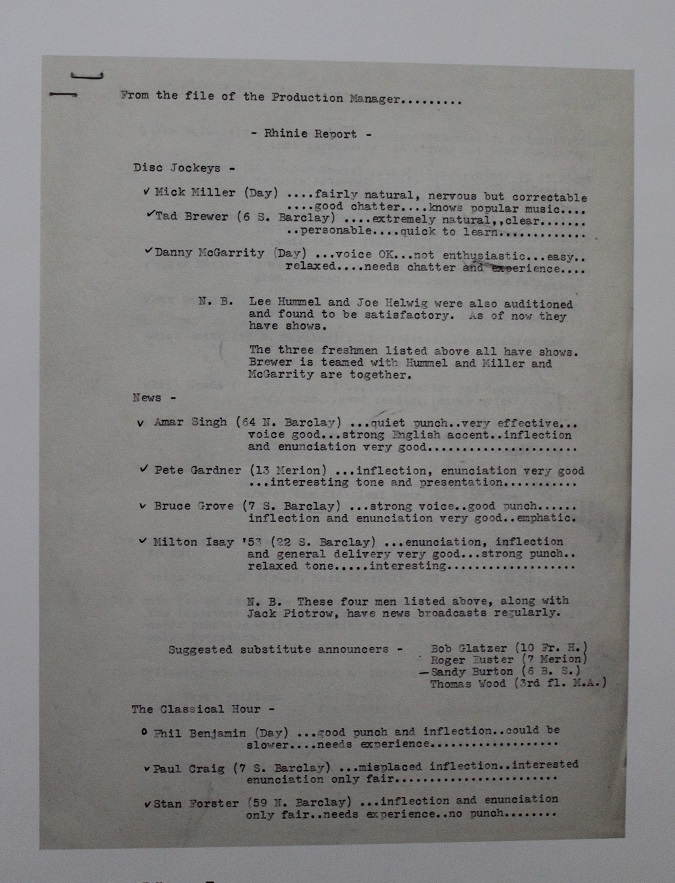

In the 1950s, when Lorenzo Milam was a DJ there, Haverford College’s student-run AM carrier current station WHRC was located in a small attic space in the Union building on campus. It aired a mix of material, including “good music” from 8pm to 9pm and “…’real music’ like calypso” at 10pm according to a 1956 student yearbook entry. “Panel discussions, drama, and assorted other innovations were rare enough to be known only to participants and their roommates,” the article continues. By the next school year, the station was on an upswing technologically and budget-wise, with a “year’s contract from Lucky Strike with a United-Press teletype as the reward, as well as new favors from the College Radio Corporation in the form of spots that paid real money.” Similar to Yale’s WYBC, as an unlicensed carrier current station, WHRC was also free to seek out these sorts of advertising deals. However, unlike WYBC, the Haverford radio station seemed a bit less structured, smaller in size, and perhaps more ramshackle; although a few years later in 1959, nearby Swarthmore College’s station WSRN was looking to WHRC for inspiration, citing WHRC’s “higher quality” programs.

A number of years back, while I was deep into my research into Haverford College radio history, I connected with Lorenzo Milam to learn more about his time at WHRC in the 1950s. A descriptive writer and excellent story-teller; he regaled me with tales over email about the broken-down college radio operation.

He shared some of the challenges of working at WHRC, telling me a few years ago that it “was a royal pain: I had polio and it was on the top floor of Founders [ed. most accounts actually place the station in Union] but (fortunately) the school installed a side-bar on the stairs up there and I was able to get to do my program every week, even those musty 15″ discs they sent from Radio Diffusion Francaise, with the turntables at our station that were so old they went wow wow wow.”

Milam provided me with even more extensive reminiscences about WHRC in an earlier email correspondence:

The thing I remember most about Haverford radio 1955 – 1957 was how tiny and miserable the studio/control room there at the top of Founder’s Hall. I also recall how dark the hallways and creepy the stairs and how crappy the dratted turntables.

They were forever slowing down in the midst of my concerts so the music would rumble down very low in register. I had to take the turntables apart and squirt solvent on the rubber wheel drives to keep them going and stop them from ratcheting down my disks from 33-1/3 rpm to 22 rpm or so. Since I had worked at a series of awful AM stations in Jacksonville, Florida (my home) I was used to wretched working conditions, but WHRC took the cake.

2014 photo by Jennifer Waits

Milam goes on to describe the lack of supervision at WHRC, which allowed the student DJs to do and play pretty much whatever they liked. This must have been a huge contrast to the situation at WYBC, with its weeks-long competitive training program. He explained, “It was generalised anarchy. There was no one to supervise things which was OK, because it meant that we could play anything we wanted — which, for me, meant endless Handel, Lully, Rameau, Mozart, Vivaldi, Soler, and the great Bach Cantatas from Westminister (with Hermann Scherchen) and the wonderful Bach Trio Sonatas for Organ from DGG Archive (Helmet Walcha). I was, as you can see, in my Baroque phase then, a phase I suppose I have never left behind…”

Interesting vintage LPs and 78s were still floating around the station when I was a student decades later and Milam described a few of them, saying, “We also played terribly dull 15″ transcriptions from Radio Diffusion Francaise and some equally dull concerts from Deutsche Weille at WHRC.”

Like so many before and after him at WHRC; Milam recounts the challenges of doing student radio at a campus-only operation, with a very small potential listening audience. Milam shared, “It was all a labor of love because it was a closed circuit transmission system — no one told us that there were FM frequencies free for the asking from the FCC — which meant that the signal barely got up enough steam to [get] out to the dorm rooms and half-way down the Nature Walk before it pooped out.”

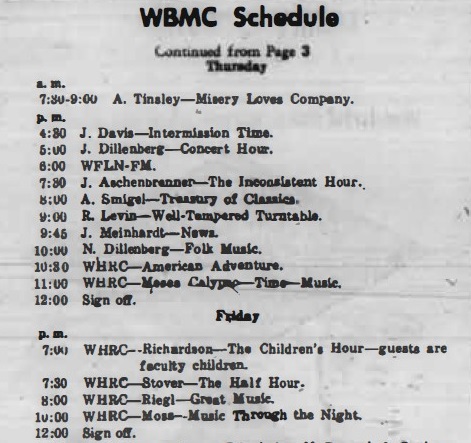

In the 1950s, WHRC broadcast to Haverford College’s dorms, the dining hall, and even to nearby Bryn Mawr College over AM carrier current. Since the earliest days of radio at Haverford College in the 1920s (initially a men’s school, it went co-ed in 1980), women from Bryn Mawr College participated in station operations. Additionally, a separate station, WBMC, operated at Bryn Mawr until about 1959 (followed by a brief revival in the early 1960s). Along with its own programming, WBMC aired material from other stations, include Haverford’s. Some of the WHRC shows that ran on WBMC in fall 1955 included “American Adventure,” “Great Music,” “Music Through the Night,” and “The Children’s Hour,” on which the guests were faculty children!

Milam recalled, “It was even more of a labor of love for the students at Bryn Mawr. The engineers at WHRC also took care of their transmitter and closed-circuit lines (women, in those days, were assumed to be ignorant of the finer workings of AM transmission) and one of the engineers confided in me in early 1956 that something had gone wrong with the wood-burning transmitter over at Bryn Mawr and — for several months — their signal went nowhere beyond their ratty studio speakers. Every now and again one of the programmers over there would ask Mr. Sparks why she couldn’t hear her own program and he would mumble something about the wiring in her room being at fault.”

A kindred radio historian, Milam also held an interest in Haverford College’s early radio history in the 1920s and its connections with radio advancements beyond the college. He pointed out to me back in 2009 that, “One of my fellow students at Haverford was Lauro Halstead, now an MD in Washington, DC. According to him, his uncle had helped Major Edwin Howard Armstrong not only develop FM, but had helped him to invent the concept of the subcarrier. Evidently this elder Halstead had built one of the first AM stations in the United States, which was licensed to Haverford College, and rather famous on the east coast where it had some coverage.”

Milam’s referencing WABQ, which launched at Haverford College in 1923 and sadly came to an end in 1927. And, yes, the elder Halstead, William S., was one of the masterminds of this very early licensed student radio station over AM and was also a key participant in the development of FM. His obituary in the New York Times pointed out that in 1950, “Mr. Halstead and a group of associates demonstrated one of the first stereo broadcasts by a single FM station.”

Milam concludes his note to me with, “But if you read REBELS ON THE AIR, it will tell you, and tell you well, how during the 1920s the commercial broadcasters gradually squeezed out the non-commercial stations by leaning on the old Federal Radio Commission to gum up assigned frequency and hours. The commercial broadcasters could avail themselves of expensive lawyers, thus out-maneuver the educators who never had enough in the till to protect their frequencies from cooption. I think that is probably why Haverford lost its powerful AM radio station sometime in the 1920s. Now there’s something that would make for a fascinating disquisition.” I couldn’t agree more and I continue to be obsessed with this early era of student-run college radio in the 1920s, as it’s another slice of hidden history.

I’m sad that I won’t be able to catch up with Lorenzo Milam again about our shared WHRC past; but I’m so thankful for these lovely stories and for all that he did for the development and expansion of community radio in the United States.