In the provocative piece, Why College Radio Still Matters, Columbia College junior Torsten Odland dissects the role of the college radio DJ today, comparing it with the presumed pinnacle of college radio DJ influence in the 1980s.

A DJ himself at Columbia College radio station WKCR-FM, Odland explains that he had a particular archetype of a college radio DJ in mind before he began working at his college radio station. He writes,

“The college radio persona I’m thinking of—the rock-nerd saving space in the airwaves for interesting pop music, the sarcastic taste-maker who may actually just be Stephen Malkmus—lives eternally in 1986, when they were socially necessary.

Though I didn’t realize that when I first started programming at WKCR, part of my motivation to get involved had to do with the role I thought I might fill as a cool one.”

He goes on to dissect the role of radio at Columbia (and Barnard College) by talking about college stations WKCR and WBAR (which I visited in 2009). He states,

“But there’s a crucial difference between the college radio stereotype and radio at Columbia today: WKCR and WBAR have very few listeners on campus and are functionally irrelevant to the taste and cultural sense of most Columbia students (insofar as they’re radio stations).”

I’m glad that Odland acknowledges that there is a stereotype about college radio’s major role in the 1980s, because it’s certainly possible that even in 1986 there were few campus listeners to most college radio stations. Many stations were campus-only operations with unpredictable broadcasts, for example. Odland argues that the potential of college radio is completely different in 2013 in large part because of the Internet. He makes an interesting point about the unlimited, free access to media that the Internet affords today. The media landscape in 1986 was so different that it’s hard for a 20-year-old to even fathom it. He writes,

“Why don’t college kids listen to the radio these days when it seemed to mean so much to them 25 years ago? Computers. If I sound pedantic, it’s because I need to remind myself periodically that before 15 years ago, human beings did not have free, instant access to all media. Anyone with a computer and Wi-Fi, even if they confine themselves to YouTube, has more music to choose from than any station library ever had, and they can listen to it in whatever order they please. If you want variety but aren’t terribly curious, Pandora can give you a mathematical approximation of the radio station you’d want to listen to anyway.”

To me one of his more intriguing points is that students today may be more drawn to music on the Internet because it gives them “the most control over what they listen to.” The idea of a DJ as musical gatekeeper may be unappealing to his generation because it has “authoritarian” overtones. I would guess that even in the 1980s there were college students who had the same feeling about college radio. Instead of tuning in to a campus station, they would frequent local record shops, craft their own mix tapes, and voraciously read music ‘zines in order to construct their own listening experiences.

As a member of Generation X (I was in college during the supposed heyday of college radio), I have a different take on the idea of who controls my music listening. I’ve always enjoyed tuning in to talented DJs who curate amazing sets of music and take me on a journey that I didn’t expect.

I continue to discover music by listening to (and by doing) college radio and like that it can work to contextualize music for me (vs. the often wide-open Internet). While I agree with Odland’s argument that, “The type of person who would have listened to college radio 25 years ago has all the tools today to be their own DJ, so to speak, and construct their own musical education,” I also believe that college radio can still serve the same purpose that it did 25 years ago.

To a certain degree Odland agrees. In his conclusion he surmises that although college radio DJs today might be less significant as far as influence goes, they do provide an important human element to music-sharing. He writes,

“There’s no pretense that I’m any kind of authority, or that the listeners need to come to me for the esoteric music they want to hear—if that’s what my audience wanted, they’d be better served by Google. Without those coercive elements, the listeners who stick around do so, presumably, because they prefer sharing musical experiences with other human beings.”

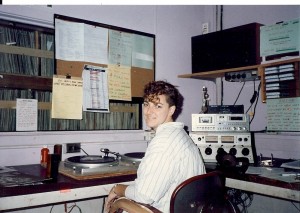

I don’t think that experience is much different from what a college radio DJ may have had in 1986. The reality is that not many college radio DJs (even in 1986) had much social influence. College radio collectively may have helped break bands, sell records, and book shows; but there were many of us DJs who had limited audiences for our individual programs. I have no illusions that my meal-time show broadcast to my college’s cafeteria had any sort of broad influence on the music taste of my classmates. That doesn’t necessarily limit the human connections that we were building, as the happy phone call from a listener has always been heartwarming to a DJ alone in the booth in a dorm basement late at night. I’m glad to hear that college radio DJs in 2013 can still experience those sorts of moments with listeners.