“Today I’d like to speak with you about the Berlin Schnauze,” declared Walter Benjamin on Radio Berlin in 1929. “This so-called big snout is the first thing that comes to mind when talking about Berliners.”

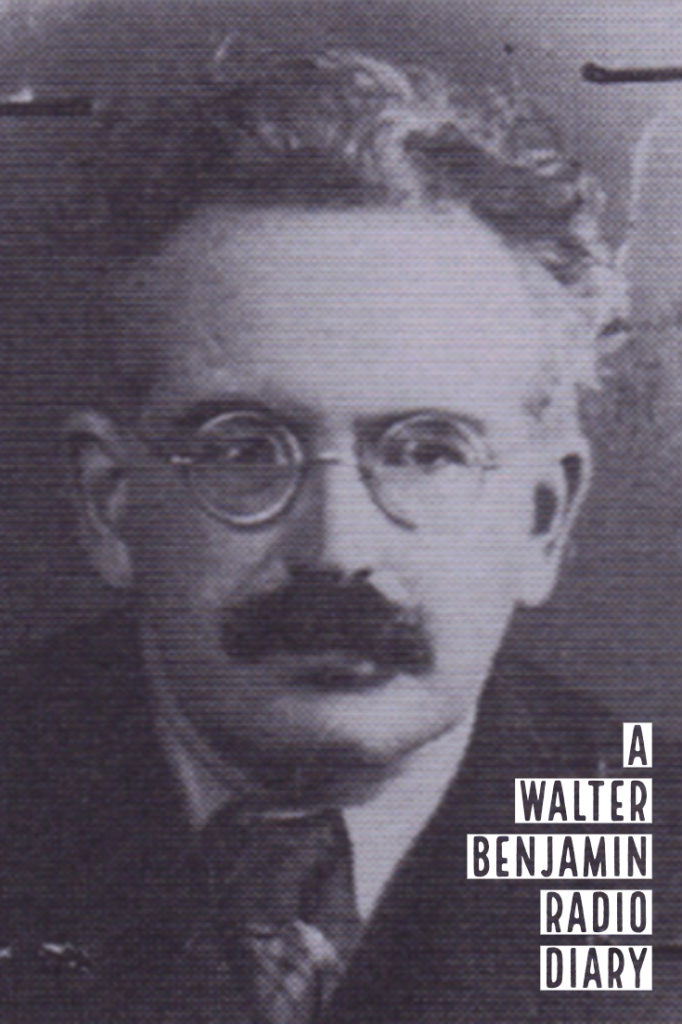

With this essay, I begin my Walter Benjamin radio diary, a commentary on the radio shows for children that he broadcast from 1929 to 1932 on Radio Berlin and Southwest German Radio, Frankfurt. I have written a brief backgrounder on Benjamin, just to get my little project started. A much better introduction can be heard at the BBC Archive on 4, produced by Michael Rosen. It includes conversations with scholars about Benjamin’s radio scripts and the very first English reading of them by Henry Goodman. I am quoting here from Lecia Rosenthal’s edition of the talks. And, full disclosure, I am really just going riff on these programs, think about them out loud, meditate on what they remind me of, while avoiding any grand conclusions.

Having said all that, Benjamin’s first radio essay is really interested in a certain portion of the Berlin snout: the Berlin mouth, with all its smarty pants jokes, comments, snarky observations, and cracks. It is a mouth designed to defend oneself from being pushed around in a pushy world. Here are some examples Benjamin offered, such as the tongue of this beleaguered horse-drawn cab operator.

“My God, driver,” complains his latest passenger. “Can’t you move a little faster?

“Sure thing,” responds the Berlin cabbie. “But I can’t just leave the horse all alone.”

Or this bartender, perhaps a bit exasperated with some of his drunken clientele.

“What ales you got?” demands one inebriant.

“I got gout and a bad back,” replies the barkeep.

“Berlinish,” Benjamin explained, “is a language that comes from work.” It is a way of speaking for “people who have no time, who must communicate by using only the slightest hint, glance, or half-word.”

I am very familiar with this language, because I grew up in the Berlin of the United States, otherwise known as New York City. I was raised on apocryphal tales of the smart assed waiters who presided over Manhattan’s Jewish restaurants and delicatessens. I offer these vignettes from memory. For example:

A waiter walks up to a table of four men in a Lowest East Side kosher restaurant. “What will you have, gentlemen?” he asks.

“We will start with water,” one says.

Then another adds with a slightly irritated tone: “And, waiter, in a clean glass, please.”

The attendant bows, then returns in five minutes with the water.

“Ok,” he says, “which one of you guys wanted the clean glass?”

Another example: a waiter humbly approaches four elderly women eating at a deli.

“Ladies,” he gingerly asks, “is anything all right?”

But what I find most interesting about Benjamin’s first commentary is that it offers a very selective and limited definition of the Schnauze. Wikipedia defines the snout as “the protruding portion of an animal’s face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw.” Yet our radio storyteller seems decidedly uninterested in two out of three of those attributes.

Why? I can only guess, but hovering over this discussion was one of the great noses of German history, that of Kaiser Wilhelm the Second. Remembered by one historian as a “bad tempered distractible doofus” in charge of the German empire, Wilhelm appears to have been primarily concerned with two things: first, his wardrobe, which consisted of 120 colorful military uniforms, and second, the endlessly waxed and fussed over mustache which adorned his nose. It even had its own name: “Er ist Erreicht.” or “It is accomplished,” which, as you may know, also happens to be the last thing that Jesus supposedly said on the cross at Golgotha. When not preoccupied with the decoration of his own beak, Wilhelm obsessed over those of his colleagues. “Fernando naso,” he dubbed King Fernando, the ruler of Bulgaria, whose proboscis he found unacceptably pronounced.

Therefore, I am not surprised that the young Walter Benjamin, already so focused on language, class, and democracy, stuck to the mouth and left the nose, with all its autocratic overtones, to others.