Thanks to Twitter, I learned about a UK ‘zine recently scanned and uploaded to the Internet Archive: “Radio Is my Bomb: a DIY Manual for Pirates.”

Published in 1987, it’s a fascinating document of the 1970s and 80s free radio in the UK and elsewhere, though principally focused on western Europe. Amusingly, the entry on the USA briefly describes the (fully licensed) Pacifica Network, noting that the community radio movement here was then about 60 stations strong. But, then concludes, “we have no information on any pirate stations in the USA.”

Alongside reports on stations and activity in different regions, there is an extensive how-to section, including a primer on radio electronics, with transmitter and antenna schematics.

What stands out is the free radio ethos espoused throughout, but especially in the introduction. It sounds no less fresh today, despite being 34 years old.

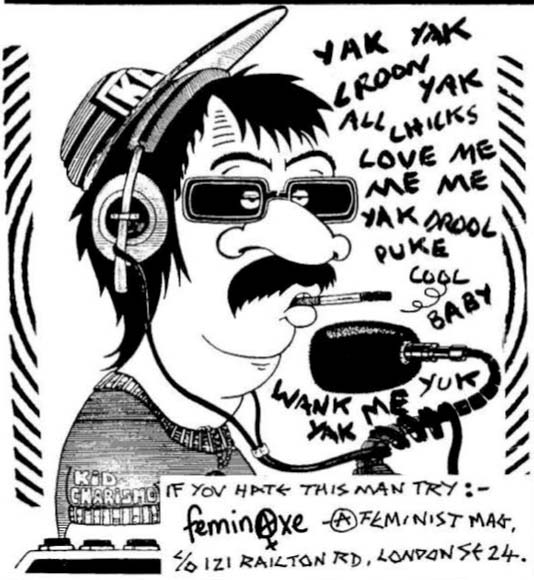

“Of course there have been radio pirates since radio was discovered,” the authors observe, “Marconi himself became the 1st pirate, when the authorities prevented him fully using his own discovery.” They go on to decry commercial radio, as well as “traditional pirate radio DJs, who tend to be all the same white sexist macho morons, preening their egos and spewing forth inane chatter in the hope of getting a fat career in the legal media.” No doubt, they have the last generation pirates – broadcasting stations like Radio Caroline – in their sights, noting that many indeed went on to long careers at the BBC and commercial radio after first sticking it to the man.

But their shots at the dinosaurs of pirate radio have a purpose beyond mere mockery. They advocate a radically more inclusive approach.

“We’d like instead to put everyone on air! To reclaim the airwaves from the parasites who infest it. We’d like to see ethnic radio, women’s radio, tenants, unions, anarchists, community groups, old people, prisoners, pacifists, urban gorillas, local info, gays, straights and of course every possible variety of musical entertainment.”

Moreover, they advocate for what something pretty close to what would become known in the US as micropower radio in the 90s, calculating evidence for its feasibility.

“We’d prefer radio chaos to the ‘aural diahorrea’ we have right now! But in fact chaos has nothing to do with it. For a start there’s plenty of room, ‘Free The Airwaves’ have calculated there’s room for 471 one mile FM pirates in London alone without interfering with anyone… We’re talking about cooperation, not chaos and competition. About open access radio, where all kinds of people can share facilities and put out occasional shows or info as they wish. We’re talking about frequency sharing, about community defence, about each ethnic group having proqrammes in their own language, etc.”

If this description also reminds you of low-power FM, it’s not a coincidence. The explosion of “micropower” community-oriented pirate radio in the 1990s helped put pressure on the FCC to create an LPFM service designed to be accessible to small community organizations.

Covering then-recent history of the pirate scenes in the UK, France, Italy, Belgium, Spain, Denmark, West Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland, El Salvador and Bolivia, “Radio Is My Bomb” is a near-encyclopedia of the movement in the 70s and 80s. While French, Italian and Dutch pirate radio are comparatively more well documented and widely cited, I was much less aware of scenes in, say, Belgium and Denmark.

I also appreciate the inclusion of Japan’s “mini TX boom,” briefly discussing the rise of “mini-FM,” as evangelized by theorist Tetsuo Kogawa. “Mini-FM” is similar to Part 15 in the US, using very low-powered transmitters that are officially legal for broadcasting without a license, due to their extremely small output and broadcast radius. However, in a dense city like Tokyo their tiny footprints still reach a sizable population, and can be used to stimulate community interaction, as with Kogawa’s “Radio Party.”

I’d love to have a print copy of “Radio Is My Bomb.” Still, thanks to a pseudonymous uploader and the Internet Archive, everyone can have a virtual copy that reminds us that the movement for freer airwaves filled with far more voices is not new, and does not end.